The following was written for the 17 April 2022 edition of my free weekly newsletter, which you can subscribe to here.

This coming week is for new ideas. Now, I can’t force new ideas, but I have processes for helping them emerge. Let me try and explain by an extended example which will show you exactly how terrible my mind is. Like:

So the last thing my collaborator threw up in conversation was ALPHAVILLE, the Jean-Luc Godard film, shot in black and white and using diegetic found light rather than the usual artificial lighting rigs. That light is nonetheless often quite high-contrast, which brought to mind the first, best and most interesting SIN CITY book, which also connects to ALPHAVILLE through its hard-boiled noir underpinning, and if you read it backwards Miller goes from the artist of the later SIN CITY books to the artist of ELEKTRA LIVES AGAIN, with dizzying one-point perspectives looking down through buildings, which made me think of Coen’s THE TRAGEDY OF MACBETH and its abstracted environments:

Which leads me off in a few different directions, like Orson Welles’ THE TRIAL, shot in the then deserted Gare D’Orsay:

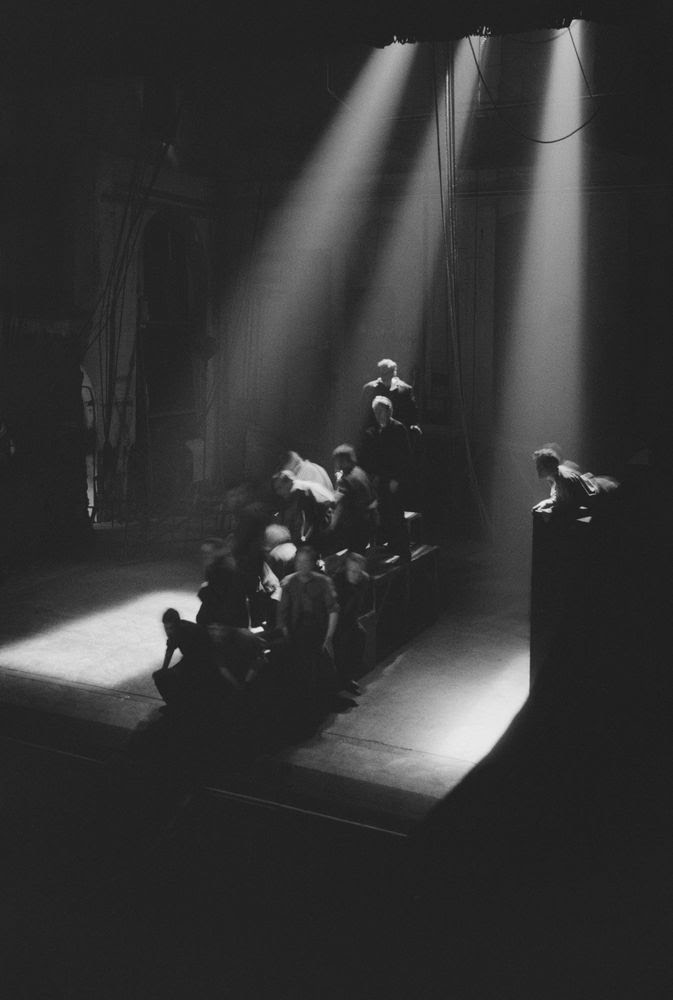

And the surviving images of Orson Welles’ black-box-theatre production of MOBY DICK (see how it pops up everywhere?):

In which Welles worked with Patrick McGoohan, whom Welles described as “intimidating,” and McGoohan once put on his own black-box production, which was the penultimate and best episode of THE PRISONER, essentially a two-hander between him and the magnificent Leo McKern (with Angelo Muscat as essential colour), who, tv myth would have it, nearly died of stress from shooting the episode. Wikipedia, in fact, says this:

According to the 2007 Don’t Knock Yourself Out documentary, during production and filming of the episode both McGoohan and McKern became totally engrossed in their roles and almost achieved a near-psychotic state (cited by various people, including Leo McKern).

It is full of very artificial lighting tricks, anxiety and paranoia. The latter two descriptors describe Kafka very well, and Tarr’s WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES to some extent, also a black and white film, also misty like Coen’s MACBETH:

There’s an abstracted environment for you.

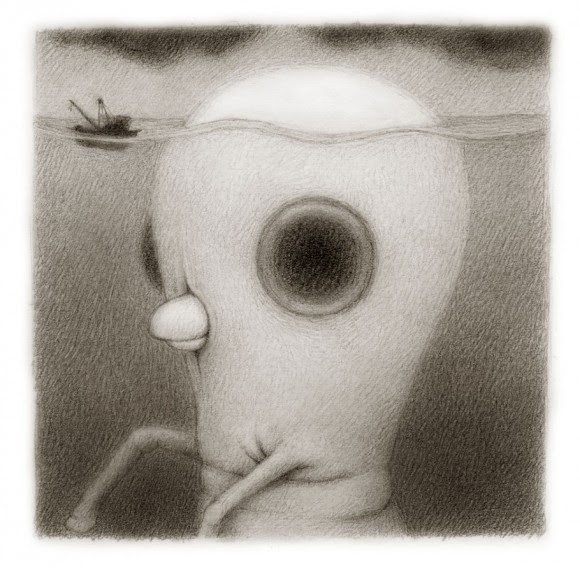

(And suddenly I’m thinking about the actual genius that is Renee French:)

Tarr started as a documentary maker, working with available light and handheld characters – just like Godard in ALPHAVILLE. Circle back to ALPHAVILLE for a second:

The contrasts, the structures and the moods they project, the strangenesses made from otherwise ordinary places and things. Even black boxes and found props. Limited settings. Limited light. ALPHAVILLE is about messing with minds. So, of course, is Macbeth – if the three fates hadn’t put the idea in his head, would he have killed Duncan? Or did he get incepted? (Unpopular opinion: TENET is Nolan’s best film, a better mind game, and it uses architecture better. It stars the son of the actor who plays Macbeth in Coen’s film.) Mind-game stories: WERCKMEISTER, and THE PRISONER, and THE TRIAL, and the whole trick of Welles’ MOBY DICK (technically, MOBY DICK – REHEARSED) is that you’re told you’re watching actors rehearse a performance of MOBY DICK but the secret of black-box theatre is that you are immersed in it until you’re tricked into seeing boxes and assemblages of people as the boat in the ocean.

What is real and what isn’t? That’s the central concern of Philip K Dick’s fiction, talking of anxiety and paranoia. (Dick’s Cold War dark half, Steve Ditko, and his 50s b/w horror comics, all sweaty fear and distrust!)

And this still from ALPHAVILLE always puts me in mind of Cocteau’s ORPHEE for some reason and I’m not going down that rabbit hole right now but I’m glad I own it on disc:

And yes, I’m free-associating through previous works of art, but I’m also thinking about the powerful effects these works had on me as I first experienced them and then as I learned more about them, and consideration of these things leads me to examine the tools they used to achieve those effects, while at the same time I’m thinking of moments in my life where I was caused to believe things that were not true, or when I could not decide when something was real or not (in the context of the thing and the moment and my brain chemistry) — and, somewhere in the middle of all that, I have a space in which to garden a story idea or two. It’s a story that grows in anxiety and paranoia, in estranged and abstracted environments, in shadows and mist. I can see the place it lives in, how it moves, and feel its weather.

When I talk about taking in as much information as you can, and then store it and let it compost in the back of your brain and make its own connections? This is part of what I’m talking about.